The 26th United Nations Climate Change conference, COP26, gets underway in Glasgow on 31 October, running through to 12 November1. Its aim is to accelerate action towards the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and as such investors should pay attention to any outcomes: they could result in policies and regulation that will affect companies and create green growth opportunities.

What to expect from the conference

COP26 has a number of key priorities, which we will explore in more depth:

- More ambitious pledges to move towards a global temperature target of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels (which is roughly equivalent to net zero)

- The mobilisation of climate finance

- Finalising Article 6

Countries to commit to more ambitious climate targets

The 2015 Paris Agreement emission reduction targets, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)2, are upgraded and improved on a five-year “ratchet” mechanism, which allows countries to raise ambitions as technologies develop and reduce in cost. Countries have collectively reduced the global temperature change implied by their pledges from 2.7 degrees warming above pre-industrial levels – the result of the initial NDCs submitted to the Paris Agreement – to 2.4 degrees over the current cycle3, which concludes with COP26. This mechanism will continue to be ratchetted down over subsequent five-year cycles, although a few notable countries such as Australia and India are yet to submit their updated NDCs.

Since the last summit, countries have also made great progress on setting net-zero targets, even though this is not a formal component of the Paris Agreement (which advocates for less than 2 degrees with the ambition of 1.5). With China and US onboard, countries representing 70% of global emissions have a net-zero pledge.4 Confusingly, however, net-zero pledges are not always reflected in a country’s NDCs. The International Energy Agency (IEA) also highlights that these net-zero targets are not yet underpinned by near‐term policies and measures, and in its recent World Energy Outlook states that today’s climate pledges would result in only 20% of the required emissions reductions by 2030 necessary to put the world on a path towards net zero by 2050.5 Hence, more and better pledges are needed.

This will be particularly relevant for the power sector, as most developed market interim net-zero targets are to achieve carbon-free electricity sectors by 2035. COP26 is also particularly focused on accelerating phasing out coal.6

COP26 therefore represents an opportunity for governments to increase their climate ambitions and definitions in terms of policies and investments, providing business with both greater certainty and detail on their net-zero commitments.

Scaling up climate finance

More than a decade ago, developed countries promised to provide $100 billion a year by 20207 to help developing countries manage the impact of climate change and invest in green energy.

However, rich countries have failed to mobilise this funding – an issue that has become a sticking point in the runup to the summit. The OECD estimates that developed countries mobilised $80 billion in total climate finance in 2019 – a shortfall of $20 billion – and recent research by the World Resources Institute found that most developed countries are not contributing their fair share toward meeting the $100 billion goal8. Three major economies, the US, Australia and Canada, provided less than half their share.

Developing countries say that without this financial support they will be unable to cut emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. It is certainly true that developing countries do not have access to the necessary levels of capital that would allow them to carry out investment in decarbonisation.

Moreover, the IEA estimates that in order to reach net-zero investment in clean energy projects and infrastructure needs to more than triple over the next decade. Some 70% of that additional spending needs to happen in emerging and developing economies where financing is scarce and capital remains up to seven times more expensive than in advanced economies.9

Developed countries are expected to pledge new climate finance at COP26 and agree on a concrete plan to deliver a minimum of $500 billion to developing nations between 2020 and 2024. But even that is unlikely to be enough. Meeting the Paris Agreement commitments of net zero by 2050 requires investments of around $5 trillion a year, or $150 trillion over 30 years, according to the IEA10.

Will COP26 deliver this promise? Some developments indicate there will at least be an increase in funding. Last month, US president Joe Biden pledged to double its contribution to $11.4 billion, but that money is for 2024 and hasn’t been approved by Congress11.

Agreement on Article 6

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement sets out the premise for international carbon trading between countries. It is in effect an international carbon market mechanism which would be governed by the UN and open to both public and private sectors, as well as “non-market” cooperation, ie development aid.

These rules around voluntary global carbon markets are the last outstanding section of the Paris Agreement “rulebook” to be finalised, with the rest of the rulebook agreed in 2018 at COP24 in Poland. Each year as the climate summit approaches, spectators become increasingly hopeful that the terms of Article 6 will be agreed. This year is no different, but could it really happen this time?

The biggest challenge regarding Article 6 is the decision around whether or not to include carbon credits established under the Kyoto Protocol. These credits are highly controversial because a lot of the emissions reductions associated with their projects are not “additional” and therefore would have happened anyway. Including them under Article 6 will incentivise countries to meet their commitments using cheap credits (priced at less than $1 per tonne) which do not drive additional decarbonisation. This would significantly weaken the impact of the Paris Agreement and increase the likelihood of missing the less-than-2 degree warming target.

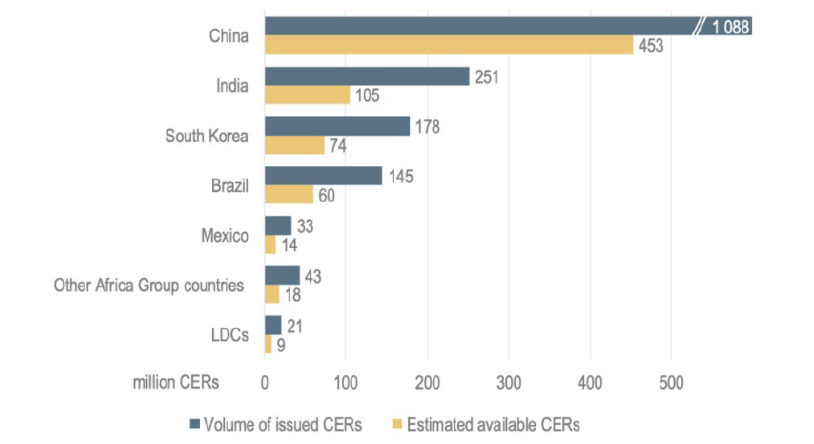

Countries that are likely to be particularly adamant on the inclusion of Kyoto-era credits are China, India, South Korea, Brazil and Mexico. This is because they collectively hold hundreds of millions of credits, called CERs, from the Kyoto era (Figure 1). Russia and Ukraine also hold significant credits from a slightly separate Kyoto-era scheme.

Countries that are likely to be particularly adamant on the inclusion of Kyoto-era credits are China, India, South Korea, Brazil and Mexico. This is because they collectively hold hundreds of millions of credits, called CERs, from the Kyoto era (Figure 1). Russia and Ukraine also hold significant credits from a slightly separate Kyoto-era scheme.

Other areas of contention within Article 6 are:

- Carbon accounting rules for the avoidance of double counting. For example, Brazil and India want to be able to count credits sold to other countries in their own emissions reductions figures.

- The automatic cancellation of credits under the international carbon market mechanism to ensure overall mitigation in global emissions. Some small island states are keen to ensure there is a schedule for cancellation. This is important because it would ensure that the market doesn’t become over saturated and ineffective. If rules are too weak there is a risk the mechanisms would be flooded by an abundance of meaningless credits.

Figure 1: Volume of CERs issued and available

Source: OECD/IEA. Number of “certified emissions reductions” (CERs) issued by each country or grouping (blue) and still available (yellow) as of 31 December 2018. LDC = group of least developed countries

All of this is important because the Kyoto agreement’s carbon trading scheme, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), is widely viewed as a failure – and there is a real risk Article

6 could suffer the same fate. Rather than driving more ambitious targets, it is widely believed that most of the emissions reductions under the CDM would have happened anyway, either because they made financial sense without credits or were required by law.

Weak emissions targets under Kyoto left many nations with a huge surplus of credits, despite not having achieved meaningful decarbonisation. An example is the economic downturn experienced in ex-Soviet union countries that saw these countries overachieve their emissions targets due to reduced productivity resulting from the downturn and were therefore granted largely meaningless credits. This phenomenon, dubbed “hot air”, has been flagged as another potential problem for the Paris Agreement.

Investment implications of COP26

Corporates

A successful COP26 outcome could provide more clarity on the future trajectory of policy and regulation and accelerate opportunities for green investments. Although agreements are high-level sovereign commitments, these have to filter down into policy in order to be achieved.

More ambitious net-zero targets underpinned by tangible measures and plans will help gauge future climate policy and regulation, providing certainty for businesses. Current ambiguity and uncertainty is delaying investment and increasing the risk of stranded assets. Businesses should therefore pay attention to the outcomes of COP26 as they will provide an insight into the conditions in which they will be operating over the next few decades.

Firm agreement around Article 6 could help set a legal framework and scale a voluntary carbon market. Barclays estimates the voluntary carbon market could reach $250 billion a year by 2030 compared to just $500 million today, and $1 trillion a year by 205013. Industries providing nature-based solutions will see growth opportunities, as well as energy, finance, agriculture and agricultural tech, and companies devoted to monitoring and verification processes. However, market awareness around greenwashing for all these options is growing quickly, so these solutions need to be well managed or risk consumer backlash.

We should also expect a wave of firmer announcements from the private sector in the wake of COP26. The summit will bring together a great number of business leaders and corporations and could be a catalyst for them to formulate firmer climate strategies independently or through industry-specific working groups, for example steel, fashion or finance, or to join organisations such as Race to Zero.

Race to Zero14 is a UN-backed global campaign aimed at encouraging non-state actors – including companies, cities, regions and financial and educational institutions – to take rigorous and immediate action to halve global emissions by 2030 and deliver a healthier, fairer zero-carbon world. The campaign is seeking to align net-zero targets among industries and set minimum standards of what a net-zero target should incorporate.

The financial sector

The financial sector in particular is in the spotlight at COP26. The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero15 brings together existing and new net-zero finance initiatives in a sector-wide coalition which aims to accelerate the transition to net-zero emissions through the alignment of lending and investment portfolios, as well as other areas of the financial system. These commitments will have implications for the broader economy as they will favour capital availability for those companies in decarbonisation mode and could begin to restrict it to those that are not aligning with net zero.

Investors should therefore be mindful about different sectors’ decarbonisation strategies as they could provide guidelines on how competition will play out, how finance will be geared and which decarbonisation solutions will be implemented, which could allow early identification of winners and losers. COP26 is also relevant for investors that are members of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative16, which consists of 128 signatories representing $43 trillion of assets under management, as they have committed to aligning their portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050. Signatories need to announce 2030 portfolio emission targets, and for those members who joined at launch this needs to be done by COP26.

Non-financial sectors

The transportation sector is expected to be a focus at COP26 with the UK, the host nation, setting an ambitious 2030 target for ending the sale of internal combustion engine vehicles. Prime minister Boris Johnson has said his focus is on “coal, cars, cash and trees” and announced £1 billion of additional electric vehicle incentives in the two-week run up to the start of the conference in order to appeal to other world leaders to make “bigger commitments”17. As yet it is unclear what the announcements might be during the summit.

Another area of attention going into the summit was methane. In August 2021 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading group of climate scientists, released an updated report18 on the physical basis of climate change. This is the first update since 2013 and outlined some concerning developments around methane. The report found that methane emissions over the last reporting period were tracking the high emission scenario published in the previous release. Although methane doesn’t remain in the atmosphere for as long as carbon dioxide does, it is a much more potent greenhouse gas: 84 times worse than carbon dioxide on a 20-year timeframe and 28 times worse on a 100-year timeframe19. High levels of methane pose a real risk to reaching 2050 net-zero emissions targets, and in some estimates the gas accounts for just under a quarter of the climate change (officially called radiative forcing) observed to-date.

All of this is relevant to the private sector because the oil and gas and agricultural industries are the biggest drivers of methane emissions. Although methane is seen as a transition fuel because it has roughly half the emissions intensity of coal when burnt, any leakage in the exploration and production of the gas quickly diminishes this benefit – again, because of the global warming potential versus carbon dioxide.

Conclusion

This climate conference is the most widely anticipated since Paris in 2015, so the stakes are high. However, signs in the lead up to it have been mixed at best. An unsuccessful summit would mean more uncertainty which would delay progress on the energy transition and the mobilisation of finance towards green investments. It could also impact progress on climate policies at national level, for example any signs of failure at COP26 could diminish President Biden’s efforts to implement his climate goals and pass climate legislation in the US.