The coronavirus outbreak is extremely complex, with the fear of the virus so far seemingly greater than its actual impact. The economic consequences, however, are very real.

The question in the headline does not refer to the Covid-19 coronavirus, rather the fear of Covid-19 that is spreading rapidly. According to Collins Dictionary a story goes viral when “it spreads quickly and widely on the internet, social media and email”. Other definitions I have read also feature references to the speed and breadth of dissemination – but not to factual accuracy.

The Covid-19 outbreak is an extremely complex situation to understand accurately at a global level as there are numerous variations and inter dependencies. Obviously, our greatest concern and sympathy must be for those people and their families directly impacted by the virus. However, to understand the potential economic and financial market impacts we need to take a detached view, creating a clear demarcation between short term and long-term/permanent impacts.

The rapidly spreading fear of Covid-19 is affecting multiple aspects of daily activity. Photographs of empty shops, roads and factories abound. Sporting events, major auto shows and other events are being cancelled, and colleges are suspending overseas study programmes. The airline industry says that personal and business travel plans are being curtailed. Images of journalists reporting while wearing face masks have become ubiquitous. Analysis of past infections such as SARS and MERS is informative but not conclusive.

This is a novel virus and therefore has novel characteristics. It appears to have a higher transmission rate, but thankfully a lower mortality rate, than other case studies. It would seem that the news of rapid spread is exacerbating fear more than the mortality rate. The dichotomy we face is the stronger the immediate containment efforts, the greater the short-term economic disruption but the greater the mitigation of long-term impacts. Consequently, the dramatic images created by containment pushes fear of Covid-19 towards hysteria.

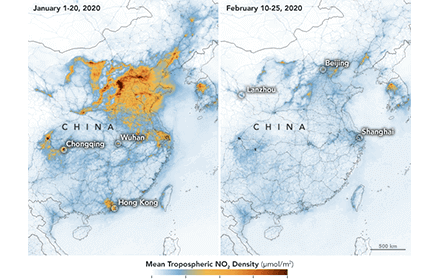

However, the reduction in economic activity is real. Perhaps the most vivid illustration was detected by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) pollution-monitoring satellites. They have “detected significant decreases in nitrogen dioxide (NO2) over China”. The images in Figure 1 show the dramatic change in NO2 from January to February following the introduction of quarantines (note that the period also includes the holiday period for Chinese New Year), implying a significant reduction in power generation, industrial activity and vehicle emissions, which is a useful proxy for an important portion of economic activity.

Short-term liquidity

The inference from the images is supported by recent comments from the American Chamber of Commerce. It notes that its members in China are reporting substantial disruption to production. Recent purchasing managers indices (PMIs) from emerging markets also indicate there is material short-term impact.

So some economic activity has been permanently lost. A simple example is eating out: if you cancelled a restaurant booking last Tuesday, it is unlikely you will eat two meals next Tuesday. Other forms of activity, however, may just be deferred. As factories resume working there may be a need for additional shifts to replenish inventory. In this case the activity was not lost but simply deferred. Nonetheless, we should not underestimate the magnitude of the short-term impact.

Consequently, the biggest risk in the short term is liquidity. If economic activity has slowed, then so too has cash flow. The focus on interest rate cuts is misplaced. Central banks have a role to play, but governments must take a prominent role in providing liquidity – Hong Kong, South Korea and Italy appear to have recognised this. At times of heightened fear, liquidity is a material issue. Therefore, providing liquidity should be the focus rather than the cost of money. Obviously the two are related, but leading with liquidity creates more policy options than leading with rates. Central banks will cut interest rates, but despite stabilising market sentiment this will have limited impact on consumer and business confidence if it is the only response.

Medium-term impacts

A medium-term issue may be the globalisation of supply chains. The creation of these has reduced cost, while just-in-time production has reduced inventories. But globalisation has also exacerbated the economic sensitivity of one country to disruption in another. While supply chains cannot be changed overnight, I suspect there is a lot of management time being spent on supply chain diversification. If lower cost was previously the primary objective, reliability and security may now feature more.

Looking to the long term

While short-term impacts exist but remain hard to quantify, long-term or permanent consequences appear limited. While the relatively high transmission rate is impacting fear levels and current activity, it is the mortality rate that will affect longer term aggregate demand and supply. Unless the mortality rate materially impacts the size of the global labour force then global economic growth will normalise reasonably quickly. This may vary between industries, and there may be winners and losers at the corporate level, but aggregate economic activity is unlikely to be affected long term. For example, it will probably take a lot longer for tourism to pick up than visits to the local grocery store. Consumers may also still distinguish between major expenditures such as cars and homes versus consumable items such as clothing.

Might online shopping and entertainment services see an additional increase in demand beyond current trends? Also, many companies have curtailed business travel, so will that resume at previous levels or will video conferencing receive a structural boost during the travel hiatus? This last point illustrates the problem with analysing the impacts of Covid-19 in isolation. As more businesses/investors seek to show their environmental, social and governance credentials, the catalyst of Covid-19 restrictions may force a thorough testing of video meetings, which is more consistent with environmental concerns around the use of aviation fuel, for example.

Understandably, the focus so far has been on Covid-19 itself. This was clearly the catalyst for the market correction, but we must acknowledge that valuations in US equity and credit markets were relatively high given the low economic and earnings growth. The risk of a recession has grown because of the short-term economic impacts of the fear of Covid-19, but the duration and depth of a recession, if it occurs, is likely to be quite short, although it may be deep in the most affected countries like China.

The aforementioned numerous global interdependencies require deep research in order to reach a conclusion, and this is where our research colleagues will focus their attention. There is a lot we still need to understand, so this is a time for careful deep research not social media speculation.